Acknowledgement

A Project on Light Emitting Diodes By Vivek Tejwani, V.Priyan, Prakash Toshniwal, Jaswant Singh, Gaurav Kumar Agrawal, Vnvm Abhinav and Kishore R, Students of IIT Indore's 2011-'15 Batch Computer Science And Engineering, guided by Mr. Manavendra Mahato (Ph.D. in University of Michigan, 2007 and B.Tech in Engineering Physics, IIT Bombay, 2001)

Wednesday 2 November, 2011

Can you guess which electronic devices is common to the above components?

Well they are SEMICONDUCTORS

Semiconductors have had a monumental impact on our society. You find semiconductors at the heart of microprocessor chips as well as transistors. Anything that's computerized or uses radio waves depends on semiconductors.

Well they are SEMICONDUCTORS

Semiconductors have had a monumental impact on our society. You find semiconductors at the heart of microprocessor chips as well as transistors. Anything that's computerized or uses radio waves depends on semiconductors.

A semiconductor is a material with electrical conductivity due to electron flow (as opposed to ionic conductivity) intermediate in magnitude between that of a conductor and an insulator. It includes transistors, solar cells, many kinds of diodes including the light- emitting diode, the silicon controlled rectifier, and digital and analog integrated circuits.

Semiconductors and insulators are distinguished from metals because the valence band in any given metal is nearly filled with electrons under usual operating conditions, while very few (semiconductor) or virtually none (insulator) of them are available in the conduction band, the band immediately above the valence band.

Today, most semiconductor chips and transistors are created with silicon. You may have heard expressions like "Silicon Valley" and the "silicon economy," and that's why -- silicon is the heart of any electronic device.

Silicon is a very common element -- for example, it is the main element in sand and quartz. If you look "silicon" up in the periodic table, you will find that it sits next to aluminum, below carbon and above germanium.

|

| Position of Silicon |

Silicon sits next to aluminum and below carbon in the periodic table.

Carbon, silicon and germanium (germanium, like silicon, is also a semiconductor) have a unique property in their electron structure -- each has four electrons in its outer orbital. This allows them to form nice crystals. The four electrons form perfect covalent bonds with four neighboring atoms, creating a lattice. In carbon, we know the crystalline form as diamond. In silicon, the crystalline form is a silvery, metallic-looking substance.

In a silicon lattice, all silicon atoms bond perfectly to four neighbors, leaving no free electrons to conduct electric current. This makes a silicon crystal an insulator rather than a conductor.

Metals tend to be good conductors of electricity because they usually have "free electrons" that can move easily between atoms, and electricity involves the flow of electrons. While silicon crystals look metallic, they are not, in fact, metals. All of the outer electrons in a silicon crystal are involved in perfect covalent bonds, so they can't move around. A pure silicon crystal is nearly an insulator -- very little electricity will flow through it.

But you can change all this through a process called doping.

Doping Silicon

The ease with which electrons in the semiconductor can be excited from the valence band to the conduction band depends on the band gap between the bands. The size of this energy bandgap serves as an arbitrary dividing line (roughly 4 eV) between semiconductors and insulators.

A pure semiconductor is often called an “intrinsic” semiconductor. The electronic properties and the conductivity of a semiconductor can be changed in a controlled manner by adding very small quantities of other elements, called “dopants”, to the intrinsic material. In crystalline silicon typically this is achieved by adding impurities of boron or phosphorus to the melt and then allowing the melt to solidify into the crystal. This process is called "doping".

Intrinsic Semiconductor: No impurities are added.

You can change the behavior of silicon and turn it into a conductor by doping it. In doping, you mix a small amount of an impurity into the silicon crystal.

There are two types of impurities:

N-type - In N-type doping, phosphorus or arsenic is added to the silicon in small quantities. Phosphorus and arsenic each have five outer electrons, so they're out of place when they get into the silicon lattice. The fifth electron has nothing to bond to, so it's free to move around. It takes only a very small quantity of the impurity to create enough free electrons to allow an electric current to flow through the silicon. N-type silicon is a good conductor. Electrons have a negative charge, hence the name N-type.

N-type and P-type silicon are not that amazing by themselves; but when you put them together, you get some very interesting behavior at the junction. That's what happens in a diode.

Electrons excited to the conduction band also leave behind electron holes, i.e. unoccupied states in the valence band. Both the conduction band electrons and the valence band holes contribute to electrical conductivity. The holes themselves don't actually move, but a neighboring electron can move to fill the hole, leaving a hole at the place it has just come from, and in this way the holes appear to move, and the holes behave as if they were actual positively charged particles.

A donor atom that activates (that is, becomes incorporated into the crystal lattice) donates weakly bound valence electrons to the material, creating excess negative charge carriers. These weakly bound electrons can move about in the crystal lattice relatively freely and can facilitate conduction in the presence of an electric field. Its known as n-type impurity.

The n and p type designations indicate which charge carrier acts as the material's majority carrier. The opposite carrier is called the minority carrier, which exists due to thermal excitation at a much lower concentration compared to the majority carrier.

EFFECT OF DOPING:

- Carrier concentration

In general, an increase in doping concentration affords an increase in conductivity due to the higher concentration of carriers available for conduction. Degenerately (very highly) doped semiconductors have conductivity levels comparable to metals and are often used in modern integrated circuits as a replacement for metal. Often superscript plus and minus symbols are used to denote relative doping concentration in semiconductors. For example, n+ denotes an n-type semiconductor with a high, often degenerate, doping concentration. Similarly, p- would indicate a very lightly doped p-type material. It is useful to note that even degenerate levels of doping imply low concentrations of impurities with respect to the base semiconductor. In crystalline intrinsic silicon, there are approximately 5×1022 atoms/cm³. Doping concentration for silicon semiconductors may range anywhere from 1013 cm−3 to 1018 cm−3. Doping concentration above about 1018 cm−3 is considered degenerate at room temperature.

- Introducing new energy levels:

Doping a semiconductor crystal introduces allowed energy states within the band gap but very close to the energy band that corresponds to the dopant type. In other words, donor impurities create states near the conduction band while acceptors create states near the valence band. The gap between these energy states and the nearest energy band is usually referred to as dopant-site bonding energy or EB and is relatively small. For example, the EB for boron in silicon bulk is 0.045 eV, compared with silicon's band gap of about 1.12 eV. Because EB is so small, it takes little energy to ionize the dopant atoms and create free carriers in the conduction or valence bands. Usually the thermal energy available at room temperature is sufficient to ionize most of the dopant.

Dopants also have the important effect of shifting the material's Fermi level towards the energy band that corresponds with the dopant with the greatest concentration. Since the Fermi level must remain constant in a system in thermodynamic equilibrium, stacking layers of materials with different properties leads to many useful electrical properties. For example, the p-n junction's properties are due to the energy band bending that happens as a result of lining up the Fermi levels in contacting regions of p-type and n-type material.

diode intro

What is a Diode?

A diode is the simplest sort of semiconductor device. Broadly speaking, a semiconductor is a material with a varying ability to conduct electrical current. Most semiconductors are made of a poor conductor that has had impurities added to it. The process of adding impurities is called doping.

In the case of LEDs, the conductor material is typically aluminum-gallium-arsenide (AlGaAs). In pure aluminum-gallium-arsenide, all of the atoms bond perfectly to their neighbors, leaving no free electrons (negatively charged particles) to conduct electric current. In doped material, additional atoms change the balance, either adding free electrons or creating holes where electrons can go. Either of these alterations make the material more conductive.

To get rid of the depletion zone, you have to get electrons moving from the N-type area to the P-type area and holes moving in the reverse direction. A modern semiconductor diode is made of a crystal of semiconductor like silicon that has impurities added to it to create a region on one side that contains negative charge carriers (electrons), called n-type semiconductor, and a region on the other side that contains positive charge carriers (holes), called p-type semiconductor.

zero bias

Equilibrium

(zero bias)

In a p–n

junction, without an external applied voltage, an equilibrium

condition is reached in which a potential difference is formed across

the junction. This potential difference is called built-in potential

Vbi.After joining p-type and n-type semiconductors, electrons near the p–n interface tend to diffuse into the p region. As electrons diffuse, they leave positively charged ions (donors) in the n region. Similarly, holes near the p–n interface begin to diffuse into the n-type region leaving fixed ions (acceptors) with negative charge. The regions nearby the p–n interfaces lose their neutrality and become charged, forming the space charge region or depletion layer

The electric field created by the space charge region opposes the diffusion process for both electrons and holes. There are two concurrent phenomena: the diffusion process that tends to generate more space charge, and the electric field generated by the space charge that tends to counteract the diffusion. The carrier concentration profile at equilibrium is shown in figure A with blue and red lines. Also shown are the two counterbalancing phenomena that establish equilibrium.

The space charge region is a zone with a net charge provided by the fixed ions (donors or acceptors) that have been left uncovered by majority carrier diffusion. When equilibrium is reached, the charge density is approximated by the displayed step function. In fact, the region is completely depleted of majority carriers (leaving a charge density equal to the net doping level), and the edge between the space charge region and the neutral region is quite sharp (see figure B, Q(x) graph). The space charge region has the same magnitude of charge on both sides of the p–n interfaces, thus it extends farther on the less doped side (the n side in figures A and B).

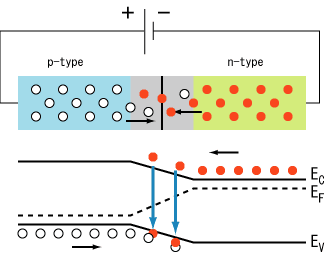

forward bias

FORWARD

BIASING:

In forward bias,

the p-type is connected with the positive terminal and the n-type is

connected with the negative terminal.With a battery connected this way, the holes in the P-type region and the electrons in the N-type region are pushed towards the junction. This reduces the width of the depletion zone. The positive charge applied to the P-type material repels the holes, while the negative charge applied to the N-type material repels the electrons. As electrons and holes are pushed towards the junction, the distance between them decreases. This lowers the barrier in potential. With increasing forward-bias voltage, the depletion zone eventually becomes thin enough that the zone's electric field can't counteract charge carrier motion across the p–n junction, consequently reducing electrical resistance. The electrons which cross the p–n junction into the P-type material (or holes which cross into the N-type material) will diffuse in the near-neutral region. Therefore, the amount of minority diffusion in the near-neutral zones determines the amount of current that may flow through the diode.

Only majority carriers (electrons in N-type material or holes in P-type) can flow through a semiconductor for a macroscopic length. With this in mind, consider the flow of electrons across the junction. The forward bias causes a force on the electrons pushing them from the N side toward the P side. With forward bias, the depletion region is narrow enough that electrons can cross the junction and inject into the P-type material. However, they do not continue to flow through the P-type material indefinitely, because it is energetically favorable for them to recombine with holes. The average length an electron travels through the P-type material before recombining is called the diffusion length, and it is typically on the order of microns.

Therefore, the macroscopic picture of the current flow through the diode involves electrons flowing through the N-type region toward the junction, holes flowing through the P-type region in the opposite direction toward the junction, and the two species of carriers constantly recombining in the vicinity of the junction. The electrons and holes travel in opposite directions, but they also have opposite charges, so the overall current is in the same direction on both sides of the diode, as required.

reverse bias

Because the p-type material is now connected to the negative terminal of the power supply, the 'holes' in the P-type material are pulled away from the junction, causing the width of the depletion zone to increase. Similarly, because the N-type region is connected to the positive terminal, the electrons will also be pulled away from the junction. Therefore the depletion region widens, and does so increasingly with increasing reverse-bias voltage. This increases the voltage barrier causing a high resistance to the flow of charge carriers thus allowing minimal electric current to cross the p–n junction. The increase in resistance of the p–n junction results in the junction behaving as an insulator.

The strength of the depletion zone electric field increases as the reverse-bias voltage increases. Once the electric field intensity increases beyond a critical level, the p–n junction depletion zone breaks-down and current begins to flow, usually by either the Zener or avalanche breakdown processes. Both of these breakdown processes are non-destructive and are reversible, so long as the amount of current flowing does not reach levels that cause the semiconductor material to overheat and cause thermal damage.

exact working or diode and its characteristics

Also, the characteristics of P-n junction diodes with change in potential difference is shown below:

Light emitting diodes, commonly called LEDs, are real unsung heroes in the electronics world. They do dozens of different jobs and are found in all kinds of devices. Among other things, they form numbers on digital clocks, transmit information from remote controls, light up watches and tell you when your appliances are turned on. Collected together, they can form images on a jumbo television screen or illuminate a traffic light.

Basically, LEDs are just tiny light bulbs that fit easily into an electrical circuit. But unlike ordinary incandescent bulbs, they don't have a filament that will burn out, and they don't get especially hot. They are illuminated solely by the movement of electrons in a semiconductor material, and they last just as long as a standard transistor. The lifespan of an LED surpasses the short life of an incandescent bulb by thousands of hours. Tiny LEDs are already replacing the tubes that light up LCD HDTVs to make dramatically thinner televisions.

In this article, we'll examine the technology behind these ubiquitous blinkers, illuminating some cool principles of electricity and light in the process.

EARLY DISCOVERIES:

Electroluminescence as a phenomenon was discovered in 1907 by the British experimenter H. J. Round of Marconi Labs, using a crystal of silicon carbide and a cat's-whisker detector.Russian Oleg Vladimirovich Losev reported creation of the first LED in 1927. His research was distributed in Russian, German and British scientific journals, but no practical use was made of the discovery for several decades.Rubin Braunstein of the Radio Corporation of America reported on infrared emission from gallium arsenide (GaAs) and other semiconductor alloys in 1955.Braunstein observed infrared emission generated by simple diode structures using gallium antimonide (GaSb), GaAs, indium phosphide (InP), and silicon-germanium (SiGe) alloys at room temperature and at 77 kelvin.

In 1961, American experimenters Robert Biard and Gary Pittman working at Texas Instruments, found that GaAs emitted infrared radiation when electric current was applied and received the patent for the infrared LED.

The first practical visible-spectrum (red) LED was developed in 1962 by Nick Holonyak Jr., while working at General Electric Company. Holonyak is seen as the "father of the light-emitting diode".M. George Craford, a former graduate student of Holonyak, invented the first yellow LED and improved the brightness of red and red-orange LEDs by a factor of ten in 1972. In 1976, T.P. Pearsall created the first high-brightness, high efficiency LEDs for optical fiber telecommunications by inventing new semiconductor materials specifically adapted to optical fiber transmission wavelengths.

Until 1968, visible and infrared LEDs were extremely costly, on the order of US $200 per unit, and so had little practical use. The Monsanto Company was the first organization to mass-produce visible LEDs, using gallium arsenide phosphide in 1968 to produce red LEDs suitable for indicators. Hewlett Packard (HP) introduced LEDs in 1968, initially using GaAsP supplied by Monsanto. The technology proved to have major uses for alphanumeric displays and was integrated into HP's early handheld calculators. In the 1970s commercially successful LED devices at under five cents each were produced by Fairchild Optoelectronics. These devices employed compound semiconductor chips fabricated with the planar process invented by Dr. Jean Hoerni at Fairchild Semiconductor. The combination of planar processing for chip fabrication and innovative packaging methods enabled the team at Fairchild led by optoelectronics pioneer Thomas Brandt to achieve the needed cost reductions. These methods continue to be used by LED producers.

The first commercial LEDs were commonly used as replacements for incandescent and neon indicator lamps, and in seven- segment displays,first in expensive equipment such as laboratory and electronics test equipment, then later in such appliances as TVs, radios, telephones, calculators, and even watches (see list of signal uses). These red LEDs were bright enough only for use as indicators, as the light output was not enough to illuminate an area. Later, other colors grew widely available and also appeared in appliances and equipment. As LED materials technology grew more advanced, light output rose, while maintaining efficiency and reliability at acceptable levels.

▪ Visual signals where light goes more or less directly from the source to the human eye, to convey a message or meaning.

▪ Illumination where light is reflected from objects to give visual response of these objects.

▪ Measuring and interacting with processes involving no human vision.[100]

▪ Narrow band light sensors where LEDs operate in a reverse-bias mode and respond to incident light, instead of emitting light.

WORKING OF AN LED

Free electrons moving across a diode can fall into empty holes from the P-type layer. This involves a drop from the conduction band to a lower orbital, so the electrons release energy in the form of photons. This happens in any diode, but you can only see the photons when the diode is composed of certain material. The atoms in a standard silicon diode, for example, are arranged in such a way that the electron drops a relatively short distance. As a result, the photon's frequency is so low that it is invisible to the human eye -- it is in the infrared portion of the light spectrum. This isn't necessarily a bad thing, of course: Infrared LEDs are ideal for remote controls, among other things.

Visible

light-emitting diodes (VLEDs), such as the ones that light up numbers

in a digital clock, are made of materials characterized by a wider

gap between the conduction band and the lower orbitals. The size of

the gap determines the frequency of the photon -- in other words, it

determines the color of the light. While LEDs are used in everything

from remote controls to the digital displays on electronics, visible

LEDs are growing in popularity and use thanks to their long lifetimes

and miniature size. Depending on the materials used in LEDs, they can

be built to shine in infrared, ultraviolet, and all the colors of the

visible spectrum in between.

Light

is a form of energy that can be released by an atom. It is made up of

many small particle-like packets that have energy and momentum but no

mass. These particles, called photons, are the most basic units of

light.

Photons

are released as a result of moving electrons. In an atom, electrons

move in orbitals around the nucleus. Electrons in different orbitals

have different amounts of energy. Generally speaking, electrons with

greater energy move in orbitals farther away from the nucleus.

For

an electron to jump from a lower orbital to a higher orbital,

something has to boost its energy level. Conversely, an electron

releases energy when it drops from a higher orbital to a lower one.

This energy is released in the form of a photon. A greater energy

drop releases a higher-energy photon, which is characterized by a

higher frequency.

Free electrons moving across a diode can fall into empty holes from the P-type layer. This involves a drop from the conduction band to a lower orbital, so the electrons release energy in the form of photons. This happens in any diode, but you can only see the photons when the diode is composed of certain material. The atoms in a standard silicon diode, for example, are arranged in such a way that the electron drops a relatively short distance. As a result, the photon's frequency is so low that it is invisible to the human eye -- it is in the infrared portion of the light spectrum. This isn't necessarily a bad thing, of course: Infrared LEDs are ideal for remote controls, among other things.

ADVANTAGES & DISADVANTAGES OF LED:

Advantages

of led:

- Color: LEDs can emit light of an intended color without using any color filters as traditional lighting methods need. This is more efficient and can lower initial costs.

- Size: LEDs can be very small (smaller than 2 mm2) and are easily populated onto printed circuit boards.

- On/Off time: LEDs light up very quickly. A typical red indicator LED will achieve full brightness in under a microsecond. LEDs used in communications devices can have even faster response times.

- Cool light: In contrast to most light sources, LEDs radiate very little heat in the form of IR that can cause damage to sensitive objects or fabrics. Wasted energy is dispersed as heat through the base of the LED.

- They don't have a filament that will burn out, so they last much longer. Additionally, their small plastic bulb makes them a lot more durable. They also fit more easily into modern electronic circuits.

- But the main advantage is efficiency. In Incandescent bulbs, the light-production process involves generating a lot of heat (the filament must be warmed). This is completely wasted energy, unless you're using the lamp as a heater, because a huge portion of the available electricity isn't going toward producing visible light. LEDs generate very little heat, relatively speaking. A much higher percentage of the electrical power is going directly to generating light, which cuts down on the electricity demands considerably.

.

Disadvantages

▪ High

initial price: LEDs are currently more expensive, price per lumen, on

an initial capital cost basis, than most conventional lighting

technologies. The additional expense partially stems from the

relatively low lumen output and the drive circuitry and power

supplies needed.

▪ Temperature

dependence: LED performance largely depends on the ambient

temperature of the operating environment. Over-driving an LED in high

ambient temperatures may result in overheating the LED package,

eventually leading to device failure. Adequate heat sinking is needed

to maintain long life. This is especially important in automotive,

medical, and military uses where devices must operate over a wide

range of temperatures, and need low failure rates.

▪ Voltage

sensitivity: LEDs must be supplied with the voltage above the

threshold and a current below the rating. This can involve series

resistors or current-regulated power supplies.

▪ Light

quality: Most cool-white LEDs have spectra that differ significantly

from a black body radiator like the sun or an incandescent light. The

spike at 460 nm and dip at 500 nm can cause the color of

objects to be perceived differently under cool-white LED illumination

than sunlight or incandescent sources, due to metamerism, red

surfaces being rendered particularly badly by typical phosphor based

cool-white LEDs. However, the color rendering properties of common

fluorescent lamps are often inferior to what is now available in

state-of-art white LEDs.

▪ Area

light source: LEDs do not approximate a “point source” of light,

but rather a lambertian distribution. So LEDs are difficult to apply

to uses needing a spherical light field. LEDs cannot provide

divergence below a few degrees. In contrast, lasers can emit beams

with divergences of 0.2 degrees or less.

▪ Electrical

Polarity: Unlike incandescent light bulbs, which illuminate

regardless of the electrical polarity, LEDs will only light with

correct electrical polarity.

▪ Blue

hazard: There is a concern that blue LEDs and cool-white LEDs are now

capable of exceeding safe limits of the so-called blue-light hazard

as defined in eye safety specifications such as ANSI/IESNA

RP-27.1–05: Recommended Practice for Photobiological Safety for

Lamp and Lamp Systems.

▪ Blue

pollution: Because cool-white LEDs (i.e., LEDs with high color

temperature) emit proportionally more blue light than conventional

outdoor light sources such as high-pressure sodium vapor lamps, the

strong wavelength dependence of Rayleigh scattering means that

cool-white LEDs can cause more light pollution than other light

sources. The International Dark-Sky Association discourages using

white light sources with correlated color temperature above 3,000

K.

▪ Droop:

The efficiency of LEDs tends to decrease as one increases current.

LED

TVs and the Future of Light Emitting Diodes

LEDs

have come a long way since the early days of lighting up digital

clock faces. In the 2000s, LCD TVs took

over the high definition market and represented a huge step over old

standard definition CRT televisions. LCD displays were even a major

step above HD rear-projection sets that weighed well over 100 pounds

( 45.4 kilos). Now LEDs are poised to make a similar jump. While LCDs

are far thinner and lighter than massive rear-projection sets, they

still use cold cathode fluorescent tubes to project a white light

onto the pixels that make up the screen. Those add weight and

thickness to the television set. LEDs solve both problems.

Have

you ever seen a a gigantic flatscreen TV barely an inch thick? If you

have, you've seen an LED television. Here's where the acronyms get a

bit confusing: those LED TVs are still LCD TVs, because the screens

themselves are comprised of liquid crystals. Technically, they're

LED-backlit LCD TVs. Instead of fluorescent tubes, LEDs shine light

from behind the screen, illuminating the pixels to create an image.

Due to the small size and low power consumption of LEDs, LED-backlit

TVs are far thinner than regular LCD sets and are also more energy

efficient. They can also provide a wider color gamut, producing more

vivid pictures.

Because

LED TVs are still in their infancy, several different types of

LED-blacklit sets are on the market -- and not all LED TVs are

created equal. Many sets use white LED edge lighting to shine light

across the display. The only real advantage afforded by these sets is

thinness. RGB LED-backlit sets, on the other hand, provide improved

color. Some configurations even allow for a technique called local

dimming, where LEDs in different parts of the display can be

brightened or dimmed independently to create a more dynamic picture. And that highlights one more great advantage of LEDs over

compact fluorescent lights: Because the LEDs can actually be

instantly toggled on and off, they produce awesome black levels in

dark scenes. Since the white fluorescent lamps have to remain on

during TV use, some light tends to bleed through and lighten the

picture in dark scenes.

In

the future, some of the most incredible uses of LEDs will actually

come from organic

light emitting diodes, or OLEDs. The organic materials used to create

these semiconductors are flexible, allowing scientists to create

bendable lights and displays. Someday, OLEDs will pave the way for

the next generation of TVs and smart phones -- can you imagine

rolling your TV up like a poster and carrying it with you anywhere?

ORGANIC LEDS

Imagine

having a high-definition TV that is 80 inches wide and

less than a quarter-inch thick, consumes less power than most TVs on

the market today and can be rolled up when you're not using it. What

if you could have a "heads up" display in your car? How

about a display monitor built into your clothing? These devices may

be possible in the near future with the help of a technology called

organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs).

OLEDs

are solid-state devices composed of thin films of organic molecules

that create light with the application of electricity. OLEDs can

provide brighter, crisper displays on electronic devices and use less

power than conventional light-emitting diodes (LEDs) or iquid

crystal displays (LCDs) used today.

OLED

Components:

Like

an LED, an OLED is a solid-state semiconductor device that is 100 to

500 nanometers thick or about 200 times smaller than a human hair.

OLEDs can have either two layers or three layers of organic material;

in the latter design, the third layer helps transport electrons from

the cathode to the emissive layer. In this article, we'll be focusing

on the two-layer design.

An

OLED consists of the following parts:

Substrate

(clear plastic, glass, foil) - The substrate supports the OLED.

Anode

(transparent) - The anode removes electrons (adds electron "holes")

when a current flows through the device.

Organic

layers - These layers are made of organic molecules or polymers.

Conducting

layer - This layer is made of organic plastic molecules that

transport "holes" from the anode. One conducting polymer

used in OLEDs is polyaniline.

Emissive

layer - This layer is made of organic plastic molecules (different

ones from the conducting layer) that transport electrons from the

cathode; this is where light is made. One polymer used in the

emissive layer is polyfluorene.

Cathode

(may or may not be transparent depending on the type of OLED) - The

cathode injects electrons when a current flows through the device.

How

do OLEDs Emit Light?

OLEDs

emit light in a similar manner to LEDs, through a process called

electrophosphorescence.

The

process is as follows:

The

battery or power supply of the device containing the OLED applies a

voltage across the OLED.

An

electrical current flows from the cathode to the anode through the

organic layers (an electrical current is a flow of electrons). The

cathode gives electrons to the emissive layer of organic molecules.

The anode removes electrons from the conductive layer of organic

molecules. (This is the equivalent to giving electron holes to the

conductive layer.)

At

the boundary between the emissive and the conductive layers,

electrons find electron holes. When an electron finds an electron

hole, the electron fills the hole (it falls into an energy level of

the atom that's missing an electron). When this happens, the

electron gives up energy in the form of a photon of light

The

OLED emits light.

The

color of the light depends on the type of organic molecule in the

emissive layer. Manufacturers place several types of organic films on

the same OLED to make color displays.

The

intensity or brightness of the light depends on the amount of

electrical current applied: the more current, the brighter the light.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)